Techniques of Cognitive Therapy

Audiologist-delivered CBT is focused on managing hyperacusis/tinnitus-related distress and patients with symptoms of co-morbid psychological disorders should be referred to mental health professionals for assessment and appropriate management of their psychological symptoms. These should be identified at the assessment stage prior to initiating the treatment. Patients should undergo psychiatric/psychological assessment/treatment at the same time or prior to their tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation, when needed.

The audiologist-delivered CBT for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis involved individual face-to-face sessions, each lasting about one hour. Table below shows a summary of the typical techniques used in each session. For details see Dr. Aazh’s paper on audiologist-delivered CBT for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis published in International Journal of Audiology.

| Summary of the interventions provided in each audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) session for management of tinnitus and/or hyperacusis. | |

|---|---|

| Session1 | Exploration of tinnitus/hyperacusis-related distress using in-depth interview Evaluation of the patient’s cognitive, behavioural and emotional reactions to tinnitus/sound and the impact these have on their life. Development of a cognitive behavioural formulation for tinnitus/hyperacusis distress Enhancement of the patient’s motivation for the therapy Offer of full CBT or discharge |

| Session2 | Design of a behavioural experiment (BE) to target and challenge troublesome thoughts Patient to complete the BE as a between-session assignment |

| Session3 | Reviewing and reflecting on the outcomes of the BE Creation of counter-statements to negative thoughts Issuing the diary of thoughts and feelings (DTF) to be filled in as a between-session assignment |

| Session4 | Reviewing of the DTF and giving help to the patient to appraise and modify the thoughts responsible for producing tinnitus/hyperacusis-related distress Issuing another DTF to be filled in as a between-session assignment |

| Session5 | Reviewing of the DTF Developing “acceptance” of tinnitus/hyperacusis Further education about CBT |

| Session6 | Reviewing and reflecting on progress Discharge |

Case formulation

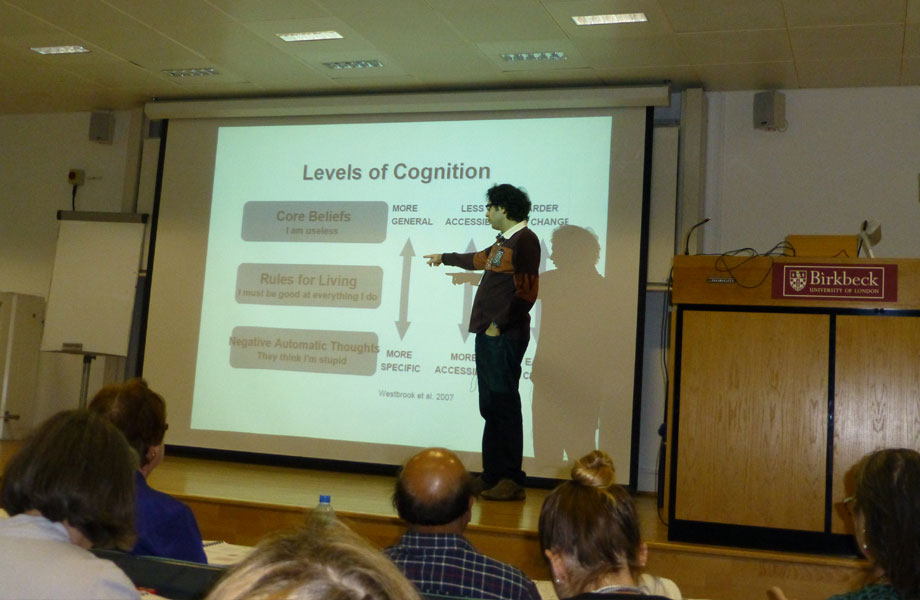

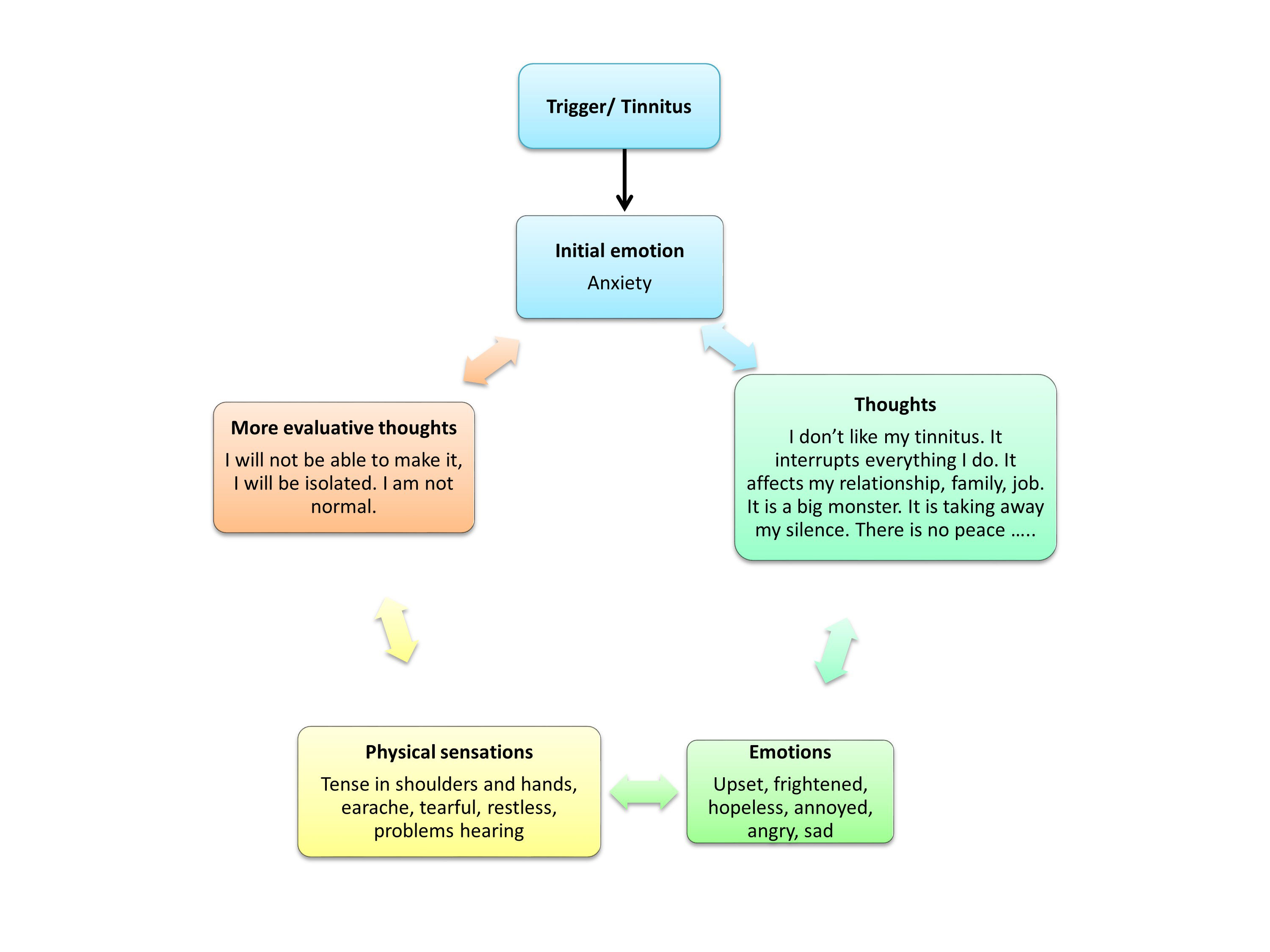

In-depth interview are used in order to explore the impact of tinnitus and/or hyperacusis on the patient’s life (Green & Thorogood 2009). If the tinnitus and/or hyperacusis does adversely affect the patient’s activities or mood then Socratic questioning should be used in order to help the patient to explore their thoughts, emotional reactions, physical sensations, and safety-seeking behaviours (SSBs). The information gathered here will be used for formulation of the processes and stages involved in producing their tinnitus and/or hyperacusis-related distress (Muran 1991). The formulation will be shared with patients and the principles of CBT will be discussed. Examples of formulation for tinnitus and hyperacusis are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The case formulations for tinnitus and hyperacusis which are proposed here begin with the initial emotional response and physical sensations related to the experience of tinnitus or hyperacusis. These initial symptoms are then followed by the individuals’ negative thoughts leading to further negative emotions, physical sensations, and evaluative thoughts which feed back into the patient’s initial reaction leading to exacerbation of their symptoms, a vicious cycle.

Behavioural experiment

Behavioural experiment (Bennett-Levy et al. 2004) should be used in order to help the patient to explore their negative predictions about what might happen to them when exposed to sounds that they found unpleasant (in the case of hyperacusis) or when they become aware of their tinnitus, and the precautions that they typically take to prevent these from happening (Bennett-Levy et al. 2004; McManus et al. 2012). The behavioural experiment provides an opportunity for the patient to drop these precautions or safety seeking behaviours (SSBs) so that they could face their fear, which is intended to help them to find out whether their negative predictions and fear are justified. Most patients state that at least some of their predictions do not come true.

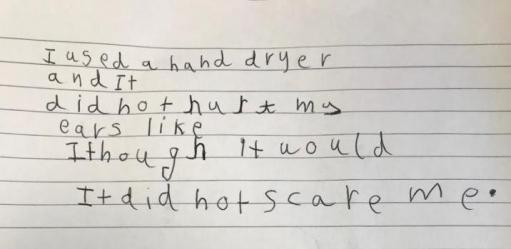

For example a 6 years old girl with hyperacusis found the classroom environment difficult due to noise levels and at times had to cover her ears. This created unnecessary stress which hampered her progress in school and impacted her self-confidence. Her mum reported that when they went to a theme park she covered her ears for almost the whole time. During the therapy she learned how to explore her thoughts and modify them. After a behavioural experiment she wrote the text below which showed her progress in resolving her intolerance to sound.

Then patients are encouraged to create counter-statements for their negative thoughts based on the evidence they gathered during the experiment (Henry & Wilson 1995). Patients are encouraged to use these counterstatements in real-life scenarios as soon as the troublesome tinnitus and/or sound-related thoughts goes through their mind.

Diary of Thoughts and Feelings (DTF)

DTF is used to provide a structured method for the patient to take notes about their tinnitus and/or sound-related problems, and their associated thoughts and emotions (Bennett-Levy 2003; McManus et al. 2012). DTF is completed by patients between sessions. During the session, audiologist use Socratic questioning style (Braun et al. 2015) to encourage the patient to think of the advantages and disadvantages of the thoughts that they recorded in the DTF, and to replace them by counter-statements if the patient decide that their thoughts were unrealistic or unhelpful. The overall approach is collaborative with a strong emphasis on the clinician and patient exploring the problem together. Throughout, the principle of guided discovery (Todd & Freshwater 1999) should be employed, in that the patient makes discoveries with the help of careful questioning from the audiologist rather than the audiologist giving information and advice.

References

Bennett-Levy, J. (2003). Mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy: the case of automatic thought records and behavioural experiments Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 31, 261-277.

Bennett-Levy, J., Butler, G., Fennell, M., et al. (2004). Oxford guide to behavioural experiments in cognitive therapy. Oxford University Press.

Braun, J. D., Strunk, D. R., Sasso, K. E., et al. (2015). Therapist use of Socratic questioning predicts session-to-session symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Behav Res Ther, 70, 32-7.

Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2009). In-depth Interviews. In Qualitative Methods for Health Research (pp. 93-122). London: Sage.

Henry, J., & Wilson, P. (1995). The psychological management of tinnitus: comparison of a combined cognitive educational program, education alone and a waiting-list control. The international tinnitus journal, 2, 9-20.

McManus, F., Van Doorn, K., & Viend, J. (2012). Examining the effects of thought records and behavioural experiments in instigating belief change. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 540-548.

Muran, J. C. (1991). A reformulation of the ABC model in cognitive psychotherapies: implications for assessment and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev, 11, 399-418.

Todd, G., & Freshwater, D. (1999). Reflective practice and guided discovery: clinical supervision. Br J Nurs, 8, 1383-9.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |