Psychology for audiologists

Certain counselling skills should be used throughout the process of specialist CBT for tinnitus & hyperacusis rehabilitation in order to build a good patient-clinician alliance, help the patient to freely talk about and explore their feelings and tinnitus/hyperacusis-related dilemmas, and to enhance and strengthen their readiness to psychologically engaging in the process of therapy. The key approaches are based on the client-cantered counselling model of Carl Rogers (Rogers 1951) and Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller 1996; Miller 1983).

Client-centred counselling

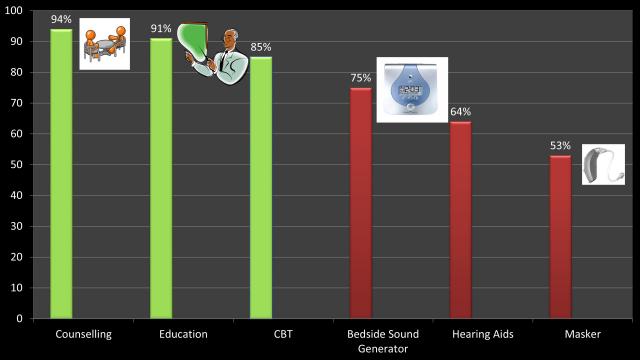

Client-centred counselling was developed by Carl Rogers (Rogers 1951) and emphasises respecting and trusting the patient’s capacity for growth, development and creativity (Rogers 1959). Empathic listening is a key counselling skill that is used throughout the therapy sessions to build a good patient-clinician relationship and offer emotional support to patients. Empathy means to understand and feel another person’s perspectives (Rogers 1959). This is different from sympathy and is completely opposite to imposing one’s own views with the assumption that patient’s views are inaccurate or misguided (Rollnick & Miller 1995). Empathic listening involves asking open-ended questions, focusing, paraphrasing, reflecting on meanings, reflecting on feelings, structuring, and summarising (Jenkins 2000). The idea is that listening empathically to a patient’s story and concerns will promote their capacity for self-growth and acceptance of tinnitus or their ability to tolerate sound. Use of client-centred counselling in the management of tinnitus and hyperacusis has been recommended by several authors (Tyler et al. 2001; Aazh et al. 2016). A pioneering study by Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team showed that based on patients’ perspectives the most effective treatment component in helping them to manage their tinnitus and/or hyperacusis was the fact that audiologist listened to them and understood their problem (Aazh 2016; Aazh et al. 2016). See the graph below which illustrates findings of the study on tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients’ evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller 1996; Miller 1983) is “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change”(Miller & Rollnick 2012, p.12). MI is rooted in the client-centred counselling method of Carl Rogers (Rogers 1959) and gives great importance to understanding of patient’s internal frame of mind and exhibiting unconditional positive regard (Miller & Baca 1983; Miller & Rose 2009). However, unlike Rogerian client-centred style where the counsellor follows the patient’s lead in a truly non-directive form and perhaps over time the counsellor moves toward clearer goals for change when they are raised by the patient, MI applies a guiding style of counselling where direction of the session is influenced by both patient and therapist in a collaborative way (Miller & Rollnick 2012).

In MI it is important to encourage the patient to explore and verbalise their reasons, need, desire and ability to change (e.g., acceptance of tinnitus as opposed to finding ways to eradicate it), as opposed to lecturing and giving them information and advice about benefits of change, or arguing about negative consequences of not making the change (Miller & Rollnick 2002). In MI, the clinician responds deferentially to the patient’s speech and the efforts are focused on evoking and strengthening the patient’s verbalised motivations and desires to change, which are called the “change talk”. The guiding style of MI, as opposed to the directive style of “informational counselling” on one end of the spectrum and to the “following style” of Carl Rogers’s client-centred counselling at the other end, helps the patient to voice the argument for change. The idea is that hearing oneself to argue for change promotes change but feeling of being pushed and confronted evokes further defence of the status quo. Providing lots of education and advice, when the patient is not ready or hasn’t asked for it, can be perceived as being pushed to do something that they may not be ready for. Patients may feel that their side of story hasn’t been heard.

In MI it is important to encourage the patient to explore and verbalise their reasons, need, desire and ability to change (e.g., acceptance of tinnitus as opposed to finding ways to eradicate it), as opposed to lecturing and giving them information and advice about benefits of change, or arguing about negative consequences of not making the change (Miller & Rollnick 2002). In MI, the clinician responds deferentially to the patient’s speech and the efforts are focused on evoking and strengthening the patient’s verbalised motivations and desires to change, which are called the “change talk”. The guiding style of MI, as opposed to the directive style of “informational counselling” on one end of the spectrum and to the “following style” of Carl Rogers’s client-centred counselling at the other end, helps the patient to voice the argument for change. The idea is that hearing oneself to argue for change promotes change but feeling of being pushed and confronted evokes further defence of the status quo. Providing lots of education and advice, when the patient is not ready or hasn’t asked for it, can be perceived as being pushed to do something that they may not be ready for. Patients may feel that their side of story hasn’t been heard.

The challenges and opportunities

Several authors addressed the need for the application of client-centred counselling skills in aural rehabilitation (Dahl et al. 1998; Laplante-Levesque et al. 2006; Ventura 1978; English & Archbold 2014; English et al. 1999; English et al. 2007; McCarthy et al. 1986; Nair & Cienkowski 2010; Searchfield et al. 2010; Stone & Olswang 1989). Despite this, there seems to be a gap in audiology training programmes and audiologists often rely on providing technical information in response to patient’s emotional reactions to the psychosocial aspects of living with their hearing impairment (English et al. 1999). Audiology programmes focus more on technological aspects of hearing aids and diagnostic procedures while patient-centred counselling aspects of service delivery often are not emphasised or ignored. Clark (2006) wrote “The person-centred practice of audiology has often taken a backseat to the more mechanical administration and interpretation of diagnostic measures and the electroacoustics of hearing instrumentation” (p.116). However, more recently there seems to be a shift towards patient-centeredness as evidenced by inclusion of counselling modules to most of the audiology training programmes in the UK and USA (English et al. 2007). The extent to which patient-centeredness occurs in routine audiology clinics is a question which needs to be investigated further (Grenness et al. 2014). It is not uncommon for audiologists to feel unprepared to utilize client-centred counselling strategies. Often due to the organisational processes and requirements, audiologists have to work with a pre-set agenda and strict time schedules for each appointment and play the dominant role in decision making (English et al. 2000; Grenness et al. 2014). For audiologists who are specialised in tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation, gaining skilfulness and in-depth knowledge of counselling skills is essential.

Audiology programmes focus more on technological aspects of hearing aids and diagnostic procedures while patient-centred counselling aspects of service delivery often are not emphasised or ignored. Clark (2006) wrote “The person-centred practice of audiology has often taken a backseat to the more mechanical administration and interpretation of diagnostic measures and the electroacoustics of hearing instrumentation” (p.116). However, more recently there seems to be a shift towards patient-centeredness as evidenced by inclusion of counselling modules to most of the audiology training programmes in the UK and USA (English et al. 2007). The extent to which patient-centeredness occurs in routine audiology clinics is a question which needs to be investigated further (Grenness et al. 2014). It is not uncommon for audiologists to feel unprepared to utilize client-centred counselling strategies. Often due to the organisational processes and requirements, audiologists have to work with a pre-set agenda and strict time schedules for each appointment and play the dominant role in decision making (English et al. 2000; Grenness et al. 2014). For audiologists who are specialised in tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation, gaining skilfulness and in-depth knowledge of counselling skills is essential.

References

Aazh, H. (2016). Patients’ experience of motivational interviewing for hearing aid use: A qualitative study embedded within a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Phonet and Audiol, 2, 1-13.

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C. J., Lammaing, K., et al. (2016). Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients’ evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments. International Journal of Audiology, 55, 514-522.

Clark, J. G. (2006). The audiology counseling growth checklist for student supervision. Seminars in Hearing, 27, 116-126.

Dahl, B., Vesterager, V., Sibelle, P., et al. (1998). Self-reported need of information, counselling and education: needs and interests of re-applicants. Scand Audiol, 27, 143-51.

English, K., & Archbold, S. (2014). Measuring the effectiveness of an audiological counseling program. Int J Audiol, 53, 115-20.

English, K., Mendel, L. L., Rojeski, T., et al. (1999). Counseling in audiology, or learning to listen: pre- and post-measures from an audiology counseling course. Am J Audiol, 8, 34-9.

English, K., Naeve-Velguth, S., Rall, E., et al. (2007). Development of an instrument to evaluate audiologic counseling skills. J Am Acad Audiol, 18, 675-87.

English, K., Rojeski, T., & Branham, K. (2000). Acquiring counseling skills in mid-career: outcomes of a distance education course for practicing audiologists. J Am Acad Audiol, 11, 84-90.

Grenness, C., Hickson, L., Laplante-Levesque, A., et al. (2014). Patient-centred care: a review for rehabilitative audiologists. Int J Audiol, 53 Suppl 1, S60-7.

Jenkins, P. (2000). Gerard Egan’s skilled helper model. In S. Palmer & R. Woolfe (Eds.), Integrative and eclectic counselling and psychotherapy (pp. 163-180). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Laplante-Levesque, A., Pichora-Fuller, M. K., & Gagne, J. P. (2006). Providing an internet-based audiological counselling programme to new hearing aid users: a qualitative study. Int J Audiol, 45, 697-706.

McCarthy, P., Culpepper, N. B., & Lucks, L. (1986). Variability in counseling experiences and training among ESB-accredited programs. Asha, 28, 49-52.

Miller, W. R. (1983). Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 11, 147-172.

Miller, W. R. (1996). Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav, 21, 835-42.

Miller, W. R., & Baca, L. M. (1983). Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy and therapist-directed controlled drinking training for problem drinkers. Behavior Therapy, 14, 441-448.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. P. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. The Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Rose, G. S. (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol, 64, 527-37.

Nair, E. L., & Cienkowski, K. M. (2010). The impact of health literacy on patient understanding of counseling and education materials. Int J Audiol, 49, 71-5.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-Centered Therapy. UK: Constable and Company Limited.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: The study of a science. Vol. 3. Formulations of the person and the social context (pp. 184-256). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rollnick, S., & Miller, W. R. (1995). What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 325-334.

Searchfield, G. D., Kaur, M., & Martin, W. H. (2010). Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those that don’t. Int J Audiol, 49, 574-9.

Stone, J. R., & Olswang, L. B. (1989). The hidden challenge in counseling. Asha, 31, 27-31.

Tyler, R. S., Haskell, G., Preece, J., et al. (2001). Nurturing patient expectations to enhance the treatment of tinnitus. Seminars in Hearing, 22, 15-21.

Ventura, F. P. (1978). Counselling the hearing-impaired geriatric patient. Patient Couns Health Educ, 1, 22-5.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |