Insomnia and tinnitus

Impact of tinnitus on sleep

It is important to explore the mechanisms underlying the association between tinnitus loudness and sleep disturbances. Tinnitus loudness is a primary attribute of tinnitus, but it is not clear whether the degree of insomnia is directly related to tinnitus loudness or whether the degree of insomnia is related to psychological factors such as annoyance or depressed mood. This can be assessed via mediation analysis (Bollen 1987). The aim of mediation analysis is to assess the direct and indirect effects of an independent variable (e.g., tinnitus loudness) on a dependent variable (e.g., insomnia). This is achieved by determining whether the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable changes when other independent variables are included in the analysis. If the other variables do change this relationship, and if they are themselves related to the dependent variable, they are known as mediator variables (Baron & Kennedy 1986).

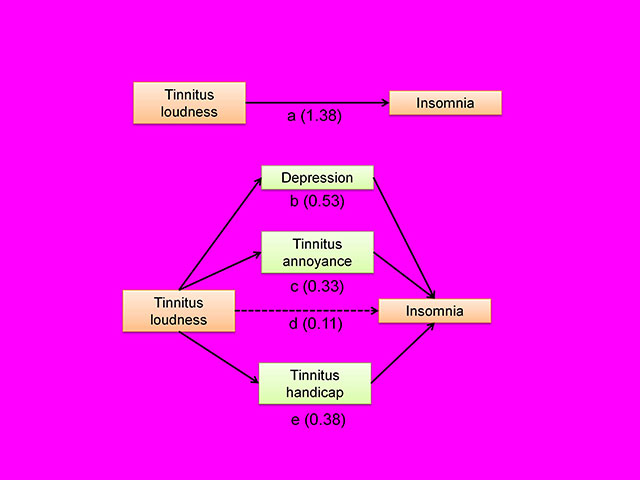

Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team studied whether there was a relationship between self-reported tinnitus loudness and insomnia and factors mediating any such relationship. A linear regression analysis using data for over 400 patients showed a statistically significant relationship between tinnitus loudness as measured via visual analogue scale (VAS) and the score on Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (b = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.7) (path “a” in Figure 1).

The outcomes of the mediation analysis are summarized in lower part of the Figure 1. The regression coefficients for the indirect effects of tinnitus loudness on insomnia were as follows: via depression (path “b” in Figure 1), b = 0.53 (95% CI: 0.35 to 0.71, p<0.001); via tinnitus annoyance (path “c” in Figure 1), b = 0.33 (95% CI: -0.004 to 0.66, p = 0.053); and via tinnitus handicap (path “e” in Figure 1), b = 0.38 (95% CI: 0.16 to 0.6, p = 0.001). The coefficient for the total indirect effect was b = 1.23 (95% CI: 0.89 to 1.58). The regression coefficient for the direct effect of tinnitus loudness on insomnia (path “d” in Figure 1) was only b = 0.11 (95% CI: -0.27 to 0.51, p = 0.57), a small and non-significant effect.

The mediation analysis showed that the relationship between tinnitus loudness and insomnia was fully mediated via depression, tinnitus handicap, and tinnitus annoyance. In other words, there was no direct effect of tinnitus loudness on insomnia. Rather, it may be the case that greater tinnitus loudness is associated with increased depression, tinnitus annoyance and tinnitus handicap, and that these in turn lead to insomnia.

One clinical implication of this finding is that, for patients who suffer from tinnitus, insomnia may be alleviated if tinnitus annoyance, tinnitus handicap and tinnitus-induced depression are managed adequately, even if the tinnitus loudness remains unchanged. Past research has shown that although various forms of tinnitus rehabilitation only minimally reduced the loudness of tinnitus, the handicap and annoyance produced by the tinnitus and depressive symptoms typically improved considerably (Aazh et al. 2008; Aazh & Moore 2016; Martinez-Devesa et al. 2010). Hence, such rehabilitation is likely to reduce problems with insomnia.

A common concern expressed by patients is that although they can cope with the current loudness of their tinnitus, their biggest fear is that if their tinnitus gets louder it may prevent them from sleeping at nights, leading to a constant state of fatigue that they would not be able to cope with. It may be helpful to such patients to inform them about the outcome of this study. They can be reassured that, although there is no proven method to decrease the loudness of tinnitus, rehabilitative procedures can reduce the impact of tinnitus on their life and decrease their emotional reaction to the tinnitus, thereby reducing the impact of tinnitus on their ability to sleep.

References

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2016). A comparison between tinnitus retraining therapy and a simplified version in treatment of tinnitus in adults. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 25, 14-23.

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C. J., & Glasberg, B. R. (2008). Simplified form of tinnitus retraining therapy in adults: a retrospective study. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord, 8, 1-7.

Baron, R. M., & Kennedy, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51, 1173-1182.

Bollen, K. A. (1987). Total, direct and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociologoical Methodology 17, 37-69.

Martinez-Devesa, P., Perera, R., Theodoulou, M., et al. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Cd005233.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |