Hearing loss and subjective tinnitus loudness

Most patients who experience tinnitus also have some form of hearing loss, but not all patients with hearing loss have tinnitus (Nicolas-Puel et al. 2002; Tyler & Baker 1983; Mazurek et al. 2010). The strong relationship between tinnitus and hearing impairment probably explains why, in the UK, 82% of tinnitus patients are referred to Audiology departments (Gander et al. 2011). To complicate matters, some people with clinically normal hearing have tinnitus (Aazh et al. 2011) suggesting that hearing loss per se not be the dominant factor for induction of tinnitus.

A common concern expressed by patients is that although they can cope with the current level of their tinnitus, one of their fears is that if their hearing worsens it may lead to an increase in tinnitus loudness that they would not be able to cope with. Audiologists typically reassure patients by explaining that there is no direct relationship between severity of hearing loss and tinnitus loudness. There are many people with clinically normal hearing who experience very loud tinnitus and people with very severe hearing loss, but no tinnitus. A compelling counter argument is people with acute hearing impairments such as an impacted wax, ear infections, acute noise exposure or those wearing hearing protection experience an increase in tinnitus loudness. Consistent with this view is the observation that ear plugging leads to decreased loudness tolerance (Formby et al. 2003). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that hearing loss severity is related to tinnitus loudness, an interpretation that is consistent with some central gain models of tinnitus and hyperacusis (Eggermont & Roberts 2004; Chen et al. 2015; Auerbach et al. 2014).

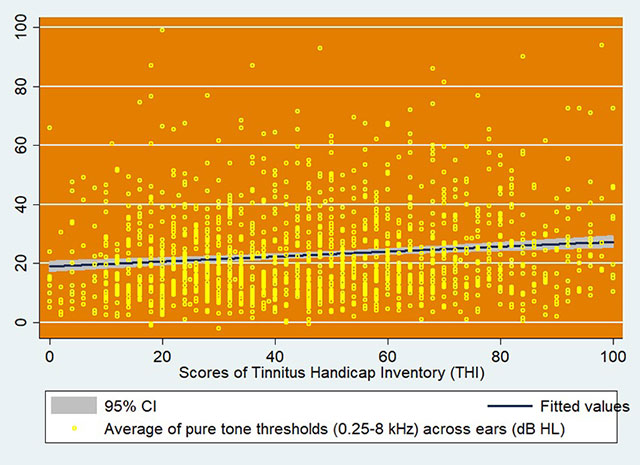

A recent analysis conducted by Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team on the data for approximately 1500 patients showed that impact of tinnitus on patient’s life as measured via Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) (Newman et al. 1996) is weakly but significantly correlated with average hearing thresholds across ears, correlation coefficient (r)=0.13 (p<0.001) (Figure 1). However this analysis doesn’t take into account the intervening effect of other factors. Therefore, it is not clear whether the relationship between hearing loss and tinnitus remains statistically significant, if the effects of other variables known to impact tinnitus are taken into account (e.g., depression, anxiety etc).

In a pioneering study, Dr Aazh’s tinnitus team assessed the relationship between tinnitus loudness and pure tone hearing thresholds while taking into account the effect of other factors among over 400 patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis (Aazh & Salvi 2018). This study is published in the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.

Hearing loss and other predicting factors for tinnitus loudness

To determine the contribution of other factors in Tinnitus Loudness as measured via visual analogue scale (VAS), we performed a stepwise linear regression analysis that, in addition to PTA threshold of the better ear, included the PTA threshold of the worse ear, ULLmin, VAS of Tinnitus Annoyance, VAS of Tinnitus Life Effect, Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), THI, Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety subscale (HADS-A), HADS-D (Depression subscale), age and gender in the linear regression model.

Nine variables did not significantly increase the proportion of variance predicted by the regression model hence were removed from the model. These were the HADS depression score (p = 0.35), PTA thresholds for the worse ear (p = 0.47), THI score (p = 0.31), HADS anxiety score (p = 0.65), ULLmin (p = 0.79), HQ score (p = 0.58), ISI score (p = 0.8), age (p = 0.08), and gender (p = 0.05).

The remaining three variables in the stepwise linear regression model that increased the proportion of variance accounted for by the model are shown in Table 1. Tinnitus Loudness was significantly associated with PTA Threshold of the better ear (t = 3.16, p<0.001, regression coefficient: 0.022). However, Tinnitus Loudness was more strongly correlated with Tinnitus Annoyance (t = 2.77, p <0.0001, regression coefficient 0.49) and Tinnitus Life Effect (t = 2.77, p<0.006, regression coefficient 0.10) than PTA threshold of the better ear. In this three-factor linear regression model, a 1-dB increase in PTA threshold of the better ear increased the Tinnitus Loudness score 0.022 units. Scores on Tinnitus Annoyance and Tinnitus Life Effect had larger effects on Tinnitus Loudness than PTA. An increase in 1 VAS unit of Tinnitus Annoyance was correlated with an increase of 0.49 VAS units of Tinnitus Loudness while an increase of 1 VAS unit of Tinnitus Life Effect was associated with an increase of 0.1 VAS unit of Tinnitus Loudness. Together, the inclusion of these three factors in the linear regression model explained 52% of the variance in Tinnitus Loudness as measured via VAS.

TABLE 1. Variables included in the final version of the stepwise linear regression model for predicting VAS tinnitus loudness together with regression coefficients, p values, and 95% CI values (n = 445).

| Regression coefficient | p value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTA of the better ear | 0.022 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.034 |

| VAS of Tinnitus Annoyance | 0.48 | < 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.57 |

| VAS of Effect of Tinnitus on Life | 0.09 | 0.006 | 0.028 | 0.17 |

Clinical Implications:

Tinnitus patients often ask whether the loudness of their tinnitus will increase if their hearing gets worse. Our results suggest that tinnitus will likely get louder, but not by very much. However, further longitudinal studies in the same subjects are needed to test the hypothesis that tinnitus will get louder as hearing loss increases. Because hearing loss increases with age and ototraumatic insults, patients should be advised to avoid loud sounds in order to preserve their hearing. However, prolonged daily use of hearing protection is not recommended because it could increase the risk that the tinnitus patient might develop hyperacusis (Aazh & Allott 2016; Formby et al. 2003). On the other hand, hearing protection should be used when noise levels equal or exceed noise safety regulations. Often patients with tinnitus feel that they should protect their hearing to avoid worsening their tinnitus. Hence, some use hearing protection on a daily basis to prevent further hearing loss. These safety-seeking behaviours likely contribute to tinnitus-related anxiety (Bennett-Levy et al. 2004; McManus et al. 2012). Safety-seeking behaviours that restrict a patient’s life experience likely contribute to tinnitus annoyance making the tinnitus “sound” even louder. Although there is no cure for tinnitus, there are a wide range of rehabilitative approaches that can minimize tinnitus annoyance and its impact on patient’s life (Aazh et al. 2016; Tyler et al. 2015). Patients who are less annoyed by their tinnitus or who feel tinnitus does not negatively affect their life have lower tinnitus loudness ratings (Aazh & Moore 2016; Aazh et al. 2008).

References

Aazh, H., & Allott, R. (2016). Cognitive behavioural therapy in management of hyperacusis: a narrative review and clinical implementation. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 25, 63-74.

Aazh, H., El Refaie, A., & Humphriss, R. (2011). Gabapentin for tinnitus: a systematic review. Am J Audiol, 20, 151-8.

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C., & Glasberg, B. R. (2008). Simplified form of tinnitus retraining therapy in adults: a retrospective study. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord, 8, 7.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2016). A comparison between tinnitus retraining therapy and a simplified version in treatment of tinnitus in adults. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 25, 14-23.

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C. J., Lammaing, K., et al. (2016). Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients’ evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments. International Journal of Audiology, 55, 514-522.

Aazh, H., & Salvi, R. (2018). The relationship between severity of hearing loss and subjective tinnitus loudness among patients seen in a specialist tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy clinic in UK Journal of American Academy of Audiology, [in press]

Auerbach, B. D., Rodrigues, P. V., & Salvi, R. J. (2014). Central gain control in tinnitus and hyperacusis. Front. Neurol., 5, 206.

Bennett-Levy, J., Butler, G., Fennell, M., et al. (2004). Oxford guide to behavioural experiments in cognitive therapy. Oxford University Press.

Chen, Y. C., Li, X., Liu, L., et al. (2015). Tinnitus and hyperacusis involve hyperactivity and enhanced connectivity in auditory-limbic-arousal-cerebellar network. Elife, 4, e06576.

Eggermont, J. J., & Roberts, L. E. (2004). The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends Neurosci, 27, 676-82.

Formby, C., Sherlock, L. P., & Gold, S. L. (2003). Adaptive plasticity of loudness induced by chronic attenuation and enhancement of the acoustic background. J Acoust Soc Am, 114, 55-8.

Gander, P. E., Hoare, D. J., Collins, L., et al. (2011). Tinnitus referral pathways within the National Health Service in England: a survey of their perceived effectiveness among audiology staff. BMC Health Serv Res, 11, 162.

Mazurek, B., Olze, H., Haupt, H., et al. (2010). The more the worse: the grade of noise-induced hearing loss associates with the severity of tinnitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 7, 3071-9.

McManus, F., Van Doorn, K., & Viend, J. (2012). Examining the effects of thought records and behavioural experiments in instigating belief change. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 540-548.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 143-8.

Nicolas-Puel, C., Faulconbridge, R. L., Guitton, M., et al. (2002). Characteristics of tinnitus and etiology of associated hearing loss: a study of 123 patients. Int Tinnitus J, 8, 37-44.

Tyler, R., Noble, W., Coelho, C., et al. (2015). Tinnitus and Hyperacusis In J. Katz, M. Chasin, K. English, L. Hood, & K. Tillery (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Audiology (pp. 647-658). Philadelphia: USA: Wolters Kluwer

Tyler, R. S., & Baker, L. J. (1983). Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. J Speech Hear Disord, 48, 150-4.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |