Effectiveness of therapy

What is CBT?

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a psychological intervention that aims to alleviate anxiety by helping the patient to modify their unhelpful, erroneous cognitions and safety-seeking behaviours (Beck 1976; Clark et al. 1999).

What is the research evidence in support of CBT for tinnitus?

Two systematic reviews have led to the conclusion that CBT delivered by psychologists in a research setting helps patients to reduce the effect of tinnitus on their lives (Martinez-Devesa et al. 2010; Hesser et al. 2011).

Specialized CBT for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis rehabilitation delivered by audiologists

Audiologist-delivered CBT is focused on managing hyperacusis/tinnitus-related distress and patients with symptoms of co-morbid psychological disorders should be referred to mental health professionals for assessment and appropriate management of their psychological symptoms. These should be identified at the assessment stage prior to initiating the treatment. Patients should undergo psychiatric/psychological assessment/treatment at the same time or prior to their tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation, when needed. Given the high prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with tinnitus/hyperacusis, most patients generally have some form of mental health treatment prior to be referred to audiology for tinnitus and hyperacusis management. If not then this should be identified promptly and appropriate actions to be taken.

In collaborative work between specialists in audiology and clinical psychology, Aazh and Allott (2016) published a protocol for audiologist-delivered CBT for hyperacusis rehabilitation. More recent studies published in the International Journal of Audiology and the American Journal of Audiology evaluated the feasibility and clinical effectiveness of CBT specialized on tinnitus and/or hyperacusis rehabilitation (Aazh & Moore 2018b; Aazh & Moore 2018a). These studies reported “medium” and “large” effect sizes (ES). The ES’s were 1.13 for tinnitus handicap inventory scores, 0.76 for hyperacusis questionnaire scores, 0.71, 0.95 and 0.93 for tinnitus loudness, annoyance and effect on life, respectively, measured using the visual analogue scale, and 0.94 for the insomnia severity index score. They concluded that audiologist-delivered CBT led to significant improvements in self-report measures of tinnitus and hyperacusis handicap and insomnia. They also suggested that methods described in these papers should be used when designing future randomized controlled trials of efficacy.

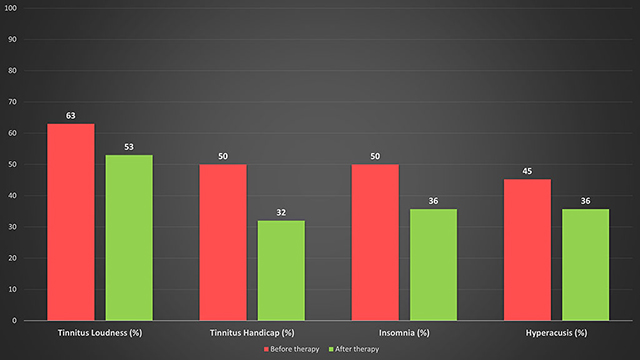

Ongoing outcome evaluations in Dr.Aazh’s tinnitus team

Figure below is the results of a recent service evaluation conducted by Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team on over 500 patients illustrating the change in the mean of tinnitus loudness, tinnitus handicap, insomnia and hyperacusis handicap as measured via Visual Analogue Scale (Adamchic et al. 2012), Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman et al. 1998), Insomnia Severity Scale (Bastien et al. 2001), and the Hyperacusis Questionnaire (Khalfa et al. 2002). All the changes were statistically significant.

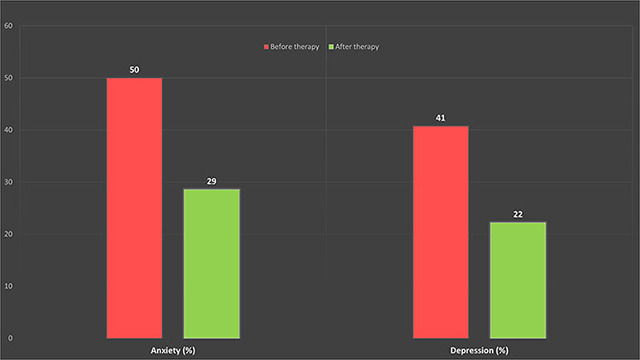

As shown in the graph below there are considerable improvements in tinnitus-related anxiety and depression scores as measured via Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al. 2006), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al. 2001), respectively. All the changes were statistically significant indicating that the anxiety and depression symptoms in this population were likely to be associated with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis hence a specialised CBT focused on minimising tinnitus and/or hyperacusis-related distress have led to improvements on GAD-7 and PHQ-9.

The Table below summarises before- and after-treatment mean scores and standard deviations (SD) on the questionnaires assessing anxiety disorders which are typically prevalent among people who experience tinnitus and/or hyperacusis/misophonia-related distress (Aazh & Moore 2017). This is on a smaller sample of patients with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis/misophonia (n=36). The tinnitus team has made recommendations for onward referrals for further psychological/psychiatric evaluations and treatment to the general practitioners (GP) of all the patients who exhibited abnormal scores on the questionnaires listed below. Most patients who exhibited abnormal scores on these questionnaires had already received some form of treatment for their anxiety disorders via GP or mental health services prior to being referred for tinnitus and/hyperacusis management.

| Questionnaire | Before treatment | After treatment | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Health Anxiety Inventory (Salkovskis et al. 2002) | 17.5 (SD=7.3) | 14 (SD=8.2) | Range: 0-54 Scores of 18 or above indicates the likely presence of health anxiety |

| MINI – SOCIAL PHOBIA INVENTORY(Connor et al. 2001) | 4.1 (SD=3) | 2.5 (SD=2.2) | Range:0-12 Scores of 6 or higher indicate possible problems with social anxiety |

| The Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory: Short Version (Foa et al. 2002) | 14.5 (SD=10.4) | 12 (SD=10.7) | Range: 0-72 Scores above 21 indicates the likely presence of obsessive compulsive disorder |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire: abbreviated version (Crittendon & Hopko 2006) | 22.6 (SD=8.2) | 20 (SD=8) | Range 0-40 Score of 23 shows symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder |

| The Panic Disorder Severity Scale – Self Report Form (Houck et al. 2002) | 6.3 (SD=6.4) | 4.6 (SD=6.4) | Range 0-28 Scores of 8 or above indicate symptoms of panic disorder |

Improvements in the measures of “general”, “social”, and “health” anxieties were statistically significant which highlights that such symptoms in this population were likely to be associated with the experience of tinnitus and/or hyperacusis hence a specialised CBT focused on minimising tinnitus and/or hyperacusis-related distress helped. It is worth mentioning that all patients with abnormal scores on the psychological questionnaires were referred to mental health services via their GP for further evaluation and treatment if needed.

However, the changes in the measures of OCD and panic disorder were not statistically significant. This suggests that it is unlikely that symptoms of OCD and panic disorders to be related to tinnitus and/or hyperacusis, therefore more specialized interventions by appropriate mental health professionals are needed. To read the research report with regard to those who need onward referral to psychological services see “the screening questionnaires for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis” study conducted by Dr. Aazh’s team in collaboration with the University of Cambridge, Department of Experimental Psychology.

References

Aazh, H., & Allott, R. (2016). Cognitive behavioural therapy in management of hyperacusis: a narrative review and clinical implementation. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 25, 63-74.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2017). Usefulness of self-report questionnaires for psychological assessment of patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis and patients’ views of the questionnaires. International Journal of Audiology, 56, 489-498.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2018a). Effectiveness of audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation: outcomes for patients treated in routine practice American Journal of Audiolgy, [Epub ahead of print], 1-12.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2018b). Proportion and characteristics of patients who were offered, enrolled in and completed audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation in a specialist UK clinic. Int J Audiol, 1-11.

Adamchic, I., Langguth, B., Hauptmann, C., et al. (2012). Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. . American Journal of Audiolgy 21, 215-225.

Bastien, C. H., Vallieres, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med, 2, 297-307.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (1999). Scientific Foundations of Cognitive Theory

and Therapy of Depression. New York: Wiley.

Connor, K. M., Kobak, K. A., Churchill, L. E., et al. (2001). Mini-SPIN: A brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety, 14, 137-40.

Crittendon, J., & Hopko, D. R. (2006). Assessing worry in older and younger adults: Psychometric properties of an abbreviated Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-A). J Anxiety Disord, 20, 1036-54.

Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Leiberg, S., et al. (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess, 14, 485-96.

Hesser, H., Weise, C., Westin, V. Z., et al. (2011). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress. Clin Psychol Rev, 31, 545-53.

Houck, P. R., Spiegel, D. A., Shear, M. K., et al. (2002). Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety, 15, 183-5.

Khalfa, S., Dubal, S., Veuillet, E., et al. (2002). Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 64, 436-42.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med, 16, 606-13.

Martinez-Devesa, P., Perera, R., Theodoulou, M., et al. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, Cd005233.

Newman, C. W., Sandridge, S. A., & Jacobson, G. P. (1998). Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol, 9, 153-60.

Salkovskis, P. M., Rimes, K. A., Warwick, H. M., et al. (2002). The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med, 32, 843-53.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., et al. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med, 166, 1092-7.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |