Depression and tinnitus

Several researchers have reported that tinnitus and hyperacusis are associated with depression (Kehrle et al. 2016; Ooms et al. 2012; Andersson et al. 2004; Hu et al. 2015; Tyler & Baker 1983). However, only a few studies have examined the factors that predict depression in patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis.

Exploration of the factors predicting depression in patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis is important as it can guide psychiatric management of the co-morbid depression in this population. Although audiology departments play a major role in offering rehabilitative interventions and support for patients experiencing tinnitus and hyperacusis (Thompson et al. 2017; Gander et al. 2011), in the UK and many other countries the psychological co-morbidities are assessed and treated by mental health services (Department of Health 2009; McKenna et al. 1991).

Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team developed the first mathematical model which explained over 60% of the variance of depression severity as measured via Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith 1983) in over 600 patients with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis (Aazh & Moore 2017). The model is presented in the table below.

| Table : Variables included in the final version of the stepwise linear regression model for predicting depression score measured with the HADS-D, together with regression coefficients, p values, and 95% CI values. Variables are listed according to the value of the regression coefficient (highest first). | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Regression coefficient | p value | 95% CI | |

| HADS-A | 0.44 | p<0.001 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| ISI | 0.13 | p<0.001 | 0.077 | 0.18 |

| HQ | 0.074 | p<0.001 | 0.036 | 0.11 |

| THI | 0.031 | p = 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.05 |

Note: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression subscale (HADS-D), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety subscale (HADS-A), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of tinnitus loudness, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

The method used to explore the process in which tinnitus loudness and hyperacusis may relate to depression

Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team used mediation analysis to assess the direct and indirect effects of tinnitus loudness (independent variable) on the depression score (dependent variable). In addition, they assessed the direct and indirect effects of reduced ULLs (independent variable) on the depression score (dependent variable). This was achieved by determining whether the relationship between a given independent variable and the dependent variable changed when other independent variables were added. If the other variables changed this relationship, and if they themselves were related to the dependent variable, they were defined as mediator variables (Baron & Kennedy 1986). The total effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable was assessed by calculating the regression coefficient (b) between them. A relationship was indicated by a regression coefficient that was significantly different from zero. If the relationship between a given independent variable, X, and the dependent variable became insignificant after including the effect of the mediator variable(s), this was defined as full mediation. Full mediation implies that the effect of X on the dependent variable is determined entirely through the mediator(s). A remaining significant effect of X after including the effect of the mediator(s) is called a direct or residual effect, and it is assumed to reflect the direct influence of X on the dependent variable (Chen & Hung 2016).

The indirect effect of a specific independent variable, X, was calculated by multiplication of the regression coefficient between X and the mediator variable, also defined as the first stage effect, and the regression coefficient between the mediator variable and the dependent variable, also defined as the second stage effect (Brown 1997). The method described by Preacher and Hayes (2008) for assessing indirect effects in multiple mediator models was used. All of the necessary coefficients were calculated via “seemingly unrelated regression” (Zellner 1962). The individual indirect effects were calculated via the “nonlinear combinations of estimators command” in STATA (Preacher & Hayes 2008). The total indirect effect was calculated by summing up the individual indirect effects (Brown 1997).

Two mediation models were developed. The first model assessed the relationship between tinnitus loudness as measured via the visual analogue scale (VAS) of tinnitus loudness and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression subscale (HADS-D) scores. The potential mediator variables were scores for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety subscale (HADS-A), Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). The second model assessed the relationship between ULLmin values (average ULL at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 kHz for the ear with the lower average ULL) and the HADS-D score. The potential mediator variables were scores for the HQ and HADS-A.

Mathematical model explaining the underlying mechanism that relate tinnitus loudness and depression

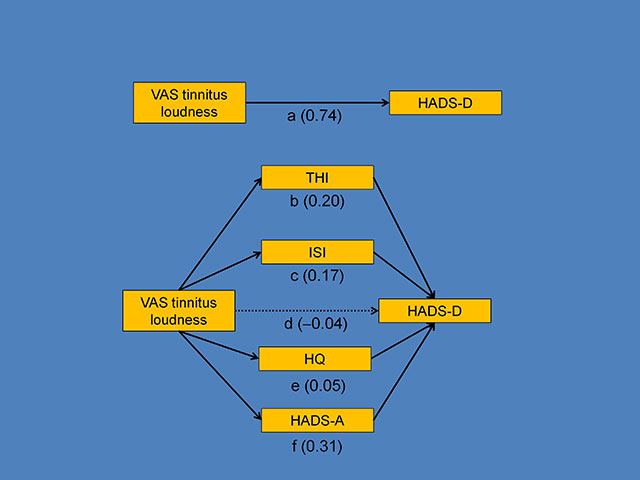

Linear regression analysis showed a statistically significant relationship between tinnitus loudness and depression (b = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55 to 0.94) (path “a” in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Multiple mediation model for the relationship between depression as measured via the HADS-D and tinnitus loudness as measured by the VAS. Numbers in parentheses are regression coefficients; see text for details.

A mediation analysis showed that the regression coefficients for the indirect effects of tinnitus loudness on depression were as follows: via tinnitus handicap (path “b”), b = 0.20 (95% CI: 0.09 to 0.32); via insomnia (path “c”), b = 0.17 (95% CI: 0.09 to 0.25); via hyperacusis (path “e”), b = 0.05 (95% CI: 0.006 to 0.085); and via anxiety (path “f”), b = 0.31 (95% CI: 0.19 to 0.42). The regression coefficient for the total indirect effect was b = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.55 to 0.92). The direct effect of tinnitus loudness on depression (path “d”) was not statistically significant (b = -0.04, 95% CI: -0.2 to 0.12). In summary, the relationship between tinnitus loudness and depression was fully mediated via tinnitus handicap, insomnia, hyperacusis, and anxiety.

The mediation model revealed that the effect of tinnitus loudness on depression, while significant, was fully mediated through scores for the THI, HQ, HADS-A and ISI. This is consistent with the idea that high tinnitus loudness is associated with tinnitus handicap, hyperacusis handicap, anxiety, and insomnia, and these in turn lead to depression. The clinical implication for audiologists is that for patients who suffer from tinnitus, depressive symptoms may be alleviated if tinnitus-induced anxiety, tinnitus handicap and hyperacusis are managed adequately, even if the self-perceived tinnitus loudness remains unchanged. Past research has shown that although tinnitus loudness as measured via the VAS is only minimally reduced following various forms of tinnitus rehabilitation, THI scores typically improve (Aazh et al. 2008; Aazh et al. 2013; Aazh & Moore 2016). This improvement may be sufficient to reduce the severity of depression.

Mathematical model explaining the underlying mechanism that relates hyperacusis and depression

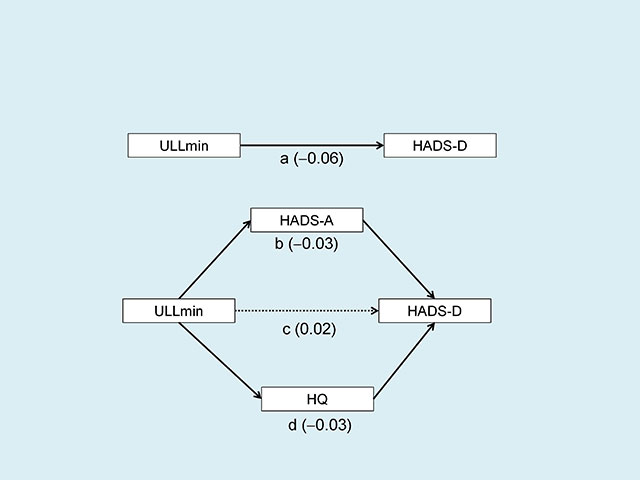

Linear regression analysis showed a small but statistically significant negative relationship between the ULLmin and depression (b = -0.06, 95% CI: -0.1 to -0.03) (path “a” in Figure 2)

Figure 2: Multiple mediation model for the relationship between depression as measured via the HADS-D and ULLmin values.

A mediation analysis showed that the regression coefficients for the indirect effects of ULLmin on depression were as follows: via anxiety (path “b”), b = -0.03 (95% CI: -0.05 to -0.013); via hyperacusis handicap (path “d”), b = -0.03 (95% CI: -0.04 to -0.014). The regression coefficient for the total indirect effect was b = -0.06 (95% CI: -0.09 to -0.03). The direct effect of the ULLmin on depression (path “c”) was not statistically significant (b = 0.02, 95% CI: -0.007 to 0.04). In summary, the relationship between ULLmin and depression was fully mediated via hyperacusis handicap and anxiety.

The second mediation model assessed the relationship between ULLmin and depression. The total effect of ULLmin values on HADS-D scores was minimal. Furthermore, the mediation model revealed that the relationship between ULLmin and HADS-D scores was mediated by hyperacusis handicap and anxiety rather than being a direct relationship. Although it has been reported that people with hyperacusis often have lower than normal ULLs in one or both ears (Tyler et al. 2014) and 42-47% of them may also suffer from depression (Goebel & Floezinger 2008; Aazh & Moore 2017), the mechanism that produces depression in patients with hyperacusis does not seem to be explained by reduced ULLs. Therefore, future research should focus on factors that might lead to depression in patients with hyperacusis.

References

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2017). Factors Associated with Depression in Patients with Tinnitus and Hyperacusis. American Journal of Audiology, 26, 562-569.

Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Kaldo, V., et al. (2004). Screening of psychiatric disorders via the Internet. A pilot study with tinnitus patients. Nord J Psychiatry, 58, 287-91.

Baron, R. M., & Kennedy, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51, 1173-1182.

Brown, R. L. (1997). Assessing specific mediational effects in complex theoretical models. Structural Equation Modeling 4, 142-156.

Chen, L.-J., & Hung, H.-C. (2016). The indirect effect in multiple mediators model by structural equation modeling. European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy 4, 36-43.

Department of Health (2009). Provision of Services for Adults with Tinnitus: A Good Practice Guide. London UK Department of Health.

Gander, P. E., Hoare, D. J., Collins, L., et al. (2011). Tinnitus referral pathways within the National Health Service in England: a survey of their perceived effectiveness among audiology staff. BMC Health Serv Res, 11, 162.

Hu, J., Xu, J., Streelman, M., et al. (2015). The correlation of the tinnitus handicap inventory with depression and anxiety in veterans with tinnitus. . Int J Otolaryngol, 2015, 689375.

Kehrle, H. M., Sampaio, A. L., Granjeiro, R. C., et al. (2016). Tinnitus annoyance in normal-hearing individuals: correlation with depression and anxiety. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 125, 185-94.

McKenna, L., Hallam, R. S., & Hinchcliffe, R. (1991). The prevalence of psychological disturbance in neuro-otology outpatients. Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences 16, 452-456.

Ooms, E., Vanheule, S., Meganck, R., et al. (2012). Tinnitus severity and its association with cognitive and somatic anxiety: a critical study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 269, 2327-33.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods 40, 879-891.

Thompson, D. M., Hall, D. A., Walker, D. M., et al. (2017). Psychological therapy for people with tinnitus: a scoping review of treatment components. Ear Hear, 38, 149-158.

Tyler, R. S., & Baker, J. L. (1983). Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48, 150-154.

Zellner, A. (1962). An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias Journal of the American Statistical Association 57, 348-368.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361-70.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |