Geriatric tinnitus and hyperacusis

It is debatable how old is old. In our research, patients over the age of 60 yrs were classified in geriatric group. This is chosen to be consistent with the age at which hearing loss tends to become sufficient to start producing problems in everyday life (Davis 1989; Agrawal et al. 2008).

Tinnitus and hyperacusis disability and handicap are related to activity limitations (e.g. problems with sleep, concentration and hearing) and participation restrictions caused by these symptoms (e.g. withdrawal from social situations, problems at work and relationship difficulties) and their impact on the individual’s psychological wellbeing and health-related quality of life (WHO 1999). Factors related to tinnitus and hyperacusis handicap may be different for older populations because the odds of hearing impairment, insomnia, anxiety, depression, cognitive and physical decline, and reduced self-perceived health-related quality of life increase with increasing age (Davis 1989; Dawes et al. 2014; McCall 2004; Lenze & Wetherell 2011). It is important to explore the factors associated with tinnitus and hyperacusis handicap in order to design appropriate rehabilitative interventions, since “cures” for these conditions are currently not available (Tyler & Baker 1983). Recent research by Dr.Aazh’s tinnitus team assessed tinnitus and hyperacusis handicap and factors associated with them for older patients. The key findings are summarised below:

Do older patients get less benefit from CBT specialised for Tinnitus and/or Hyperacusis Rehabilitation?

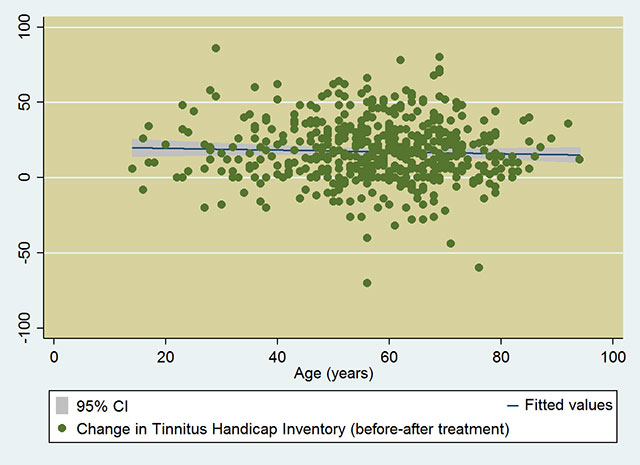

Sometimes patients ask if there is an optimum age to receive therapy for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis. Often older patients may be reluctant to undergo treatment as they may think it is too late for achieving considerable improvement due to their age (Aazh & Moore 2018b). Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team explored the relationship between the changes in tinnitus handicap as measured via Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) (Newman et al. 1996) before and after audiologist-delivered CBT and age in over 500 patients. As shown in the scatter plots, there was no statistically significant correlation between the change in THI following treatment and age (r=-0.04, p=0.33). This highlights that regardless of the age, patients may benefit from the treatment.

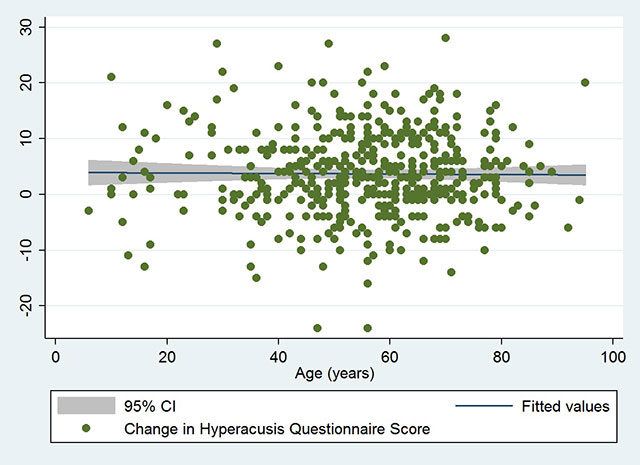

Dr. Aazh’s tinnitus team also explored the relationship between the changes in hyperacusis handicap as measured via Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ) (Khalfa et al. 2002) before and after audiologist-delivered CBT and age in over 500 patients. Their results showed no statistically significant correlation between the change in HQ following treatment and age (r=-0.01, p=0.82) (shown in the scatter plot). So it is important to highlight that patients may benefit from the treatment regardless of their age.

Should we use hearing aids to minimise tinnitus handicap?

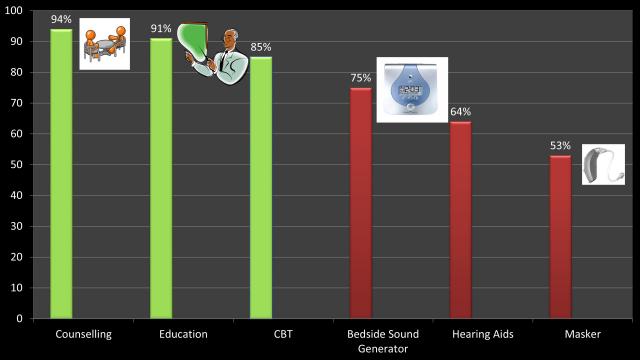

Despite the high prevalence of tinnitus among patients with hearing loss and vice versa, our result did not show a significant relationship between the pure tone audiogram and THI in patients over the age of 60. This outcome is consistent with previous studies which did not have a focus on older patients (Gomaa et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2015; Ratnayake et al. 2009). Nevertheless, when older patients complain of tinnitus, their hearing should be assessed, as recommended by the UK Good Practice Guide (Department of Health 2009) on the provision of services for adults with tinnitus and the Clinical Practice Guideline for Tinnitus of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (Tunkel et al. 2014). Fitting of hearing aids to address hearing impairment may or may not reduce the tinnitus handicap. In a study that assessed patients’ perspectives on the effectiveness of various clinical interventions in the management of tinnitus and hyperacusis (Aazh et al. 2016), use of hearing aids was rated as ineffective by 36% of patients, and all of those who reported that hearing aids were effective also reported that the counselling component of their treatment was effective in the management of their tinnitus or hyperacusis (see the bar diagram). Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the hearing aids were an effective component of the treatment package.

What are the key factors related to tinnitus handicap? “Tinnitus loudness vs. Tinnitus Annoyance”

There are conflicting results concerning the relationship between tinnitus loudness and tinnitus handicap. Some authors reported no relationship (Folmer et al. 1999; Meikle et al. 1984; Hiller & Goebel 2007) and some reported a significant relationship (Tyler et al. 2014; Probst et al. 2016; Hiller & Goebel 2006). In our study, there was a significant correlation between tinnitus loudness and THI score, but tinnitus loudness as measured via Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) did not predict tinnitus handicap in the multiple-regression model, while tinnitus annoyance as measured via VAS did. This highlights the relevance of audiologist-delivered CBT for tinnitus (Aazh & Allott 2016; Aazh & Moore 2018b; Aazh & Moore 2018a). During CBT, specialist audiologist uses careful questioning and empathic listening skills in order to help the patient to explore the underlying mechanism in which tinnitus produces annoyance and help them to modify that.

Is insomnia in older patients related to tinnitus or to depression?

In our study on 151 tinnitus patients age>60 years, a multiple linear-regression model showed that higher scores on the insomnia severity index (ISI) (Bastien et al. 2001) were associated with higher (worse) scores on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith 1983) (p=0.007). A 1-point increase in the mean HADS score for depression was associated with an increase in ISI score of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.13 to 0.79). This model explained 32% of the variance in the total ISI scores. As shown by the regression model in Table, scores for the ISI were not predicted by VAS scores for tinnitus loudness (p = 0.15), VAS scores for tinnitus annoyance (p = 0.6), scores for the anxiety subscale of the HADS (p = 0.6) or THI scores (p = 0.053).

Outcome of the multiple regression model for predicting insomnia as measured via the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

|

Regression coefficient (b) |

p value |

95% CI |

||

|

VAS (Tinnitus loudness) |

0.45 |

0.15 |

-0.2 |

1.1 |

|

VAS (Tinnitus annoyance) |

0.2 |

0.6 |

-0.55 |

0.9 |

|

VAS (Effect on life) |

-0.25 |

0.5 |

-0.99 |

0.5 |

|

HADS (Anxiety) |

0.07 |

0.63 |

-0.2 |

0.34 |

|

HADS (Depression) |

0.47 |

0.007 |

0.13 |

0.82 |

|

THI |

0.07 |

0.053 |

-0.001 |

0.15 |

VAS = visual analogue scale, HADS = hospital anxiety and depression scale, THI = tinnitus handicap inventory

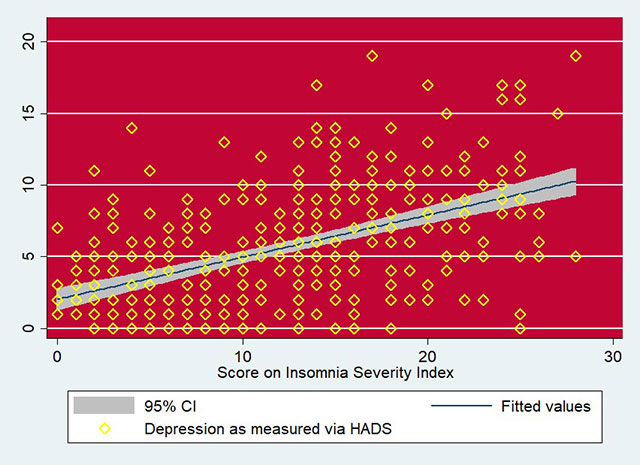

As shown in the scatter plot, insomnia in older people was significantly predicted by depression scores in our study. It is known that depression is more prevalent in older than in younger people (Mirowsky & Ross 1992). A relationship between depression and insomnia in older people has been suggested by several researchers (Foley et al. 1995; McCall 2004). If insomnia does not contribute directly to tinnitus handicap in older people, then it may not be necessary to address insomnia in the context of tinnitus rehabilitation. Perhaps insomnia needs to be assessed and managed independently from tinnitus in conjunction with treatment for depression. It is unlikely that using distractions sounds generated via bedside sound generators offer a reliable solution for insomnia in older tinnitus patients.

What are the factors related to hyperacusis handicap in older patients?

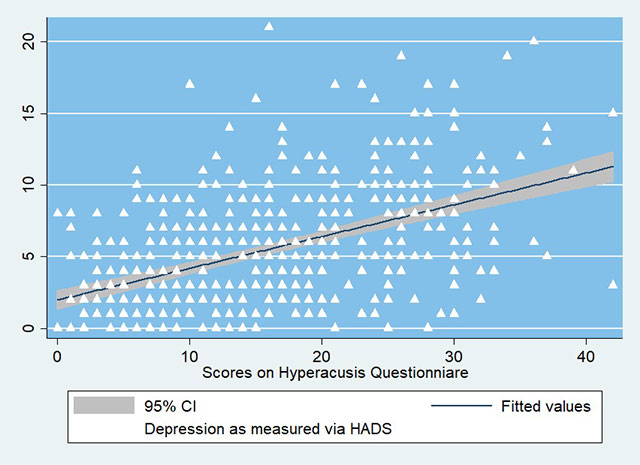

Our study in patients over the age of 60 with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis showed that depression as measured via the HADS was the main predictor of hyperacusis handicap as measured via the HQ for an older population (see the table for regression model). This highlights the need for psychological assessment in older patients who experience hyperacusis. The scatter plot illustrates a more recent analysis by Dr.Aazh’s tinnitus team on the relationship between depression and hyperacusis involving over 400 patients.

Regression model for predicting hyperacusis handicap as measured via the Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ)

|

Regression coefficient (b) |

p value |

95% CI |

||

|

THI |

0.07 |

0.048 |

0.0005 |

0.14 |

|

HADS (Anxiety) |

0.14 |

0.44 |

-0.22 |

0.49 |

|

HADS (Depression) |

0.81 |

<0.001 |

0.37 |

1.25 |

THI = tinnitus handicap inventory, HADS = hospital anxiety and depression scale

Dr. Aazh’s pioneering study challenged the view proposed by the eminent psychologist, Professor Aaron Beck, that patients’ adverse reactions to ordinary sounds are directly dependent on their anxiety levels.

The hypothesis that hyperacusis is related to anxiety has been suggested by several authors. For example, Lader et al. (1967) compared the reactions of people with various phobias and a normal control group to sequences of 1-kHz tones presented at a level of 100 dB (the authors did not state whether the level was specified as SPL or HL). The anxious group showed progressive increases in sweating, suggesting an increase in anxiety produced by the sounds, while the control group did not show such increases. Beck (1976) suggested that people with anxiety neurosis do not discriminate between safe and non-safe stimuli. Rather, any sound may be interpreted as a danger signal, leading to further anxiety.

The regression analysis of our data suggested that anxiety does not directly lead to hyperacusis handicap; rather the hyperacusis handicap is predicted by depression. This finding is not consistent with the view that patients’ adverse reactions to ordinary sounds are directly dependent on their anxiety levels. We are not aware of any study in the literature that assessed whether anxiety directly predicts hyperacusis handicap in any age group. It is known that anxiety symptoms may lead to depressive symptoms with increasing age (Wetherell et al. 2001; Lenze & Wetherell 2011). This may explain the significant role of depression in predicting hyperacusis handicap shown in the current study.

References

Aazh, H., & Allott, R. (2016). Cognitive behavioural therapy in management of hyperacusis: a narrative review and clinical implementation. Auditory and Vestibular Research, 25, 63-74.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2018a). Effectiveness of audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation: outcomes for patients treated in routine practice American Journal of Audiolgy, [Epub ahead of print], 1-12.

Aazh, H., & Moore, B. C. J. (2018b). Proportion and characteristics of patients who were offered, enrolled in and completed audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus and hyperacusis rehabilitation in a specialist UK clinic. Int J Audiol, 1-11.

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C. J., Lammaing, K., et al. (2016). Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a UK National Health Service audiology department: Patients’ evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments. International Journal of Audiology, 55, 514-522.

Agrawal, Y., Platz, E. A., & Niparko, J. K. (2008). Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med, 168, 1522-30.

Bastien, C. H., Vallieres, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med, 2, 297-307.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

Davis, A. C. (1989). The prevalence of hearing impairment and reported hearing disability among adults in Great Britain. Int J Epidemiol, 18, 911-7.

Dawes, P., Fortnum, H., Moore, D. R., et al. (2014). Hearing in middle age: a population snapshot of 40- to 69-year olds in the United Kingdom. Ear Hear, 35, e44-51.

Department of Health (2009). Provision of Services for Adults with Tinnitus: A Good Practice Guide. London UK Department of Health.

Foley, D. J., Monjan, A. A., Brown, S. L., et al. (1995). Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep, 18, 425-32.

Folmer, R. L., Griest, S. E., Meikle, M. B., et al. (1999). Tinnitus severity, loudness, and depression. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 121, 48-51.

Gomaa, M. A., Elmagd, M. H., Elbadry, M. M., et al. (2014). Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in patients with tinnitus and hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 271, 2177-84.

Hiller, W., & Goebel, G. (2006). Factors influencing tinnitus loudness and annoyance. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 132, 1323-30.

Hiller, W., & Goebel, G. (2007). When tinnitus loudness and annoyance are discrepant: audiological characteristics and psychological profile. Audiol Neurootol, 12, 391-400.

Hu, J., Xu, J., Streelman, M., et al. (2015). The correlation of the tinnitus handicap inventory with depression and anxiety in veterans with tinnitus. . Int J Otolaryngol, 2015, 689375.

Khalfa, S., Dubal, S., Veuillet, E., et al. (2002). Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 64, 436-42.

Lader, M. H., Gelder, M. G., & Marks, I. M. (1967). Palmar skin conductance measures as predictors of response to desensitization. J Psychosom Res, 11, 283-90.

Lenze, E. J., & Wetherell, J. L. (2011). A lifespan view of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 13, 381-99.

McCall, W. V. (2004). Sleep in the elderly: burden, diagnosis, and treatment. . Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 6, 9-20.

Meikle, M. B., Vernon, J., & Johnson, R. M. (1984). The perceived severity of tinnitus. Some observations concerning a large population of tinnitus clinic patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 92, 689-96.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. J Health Soc Behav, 33, 187-205; discussion 206-12.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 122, 143-8.

Probst, T., Pryss, R., Langguth, B., et al. (2016). Emotional states as mediators between tinnitus loudness and tinnitus distress in daily life: Results from the “TrackYourTinnitus” application. Sci Rep, 6, 20382.

Ratnayake, S. A., Jayarajan, V., & Bartlett, J. (2009). Could an underlying hearing loss be a significant factor in the handicap caused by tinnitus? Noise Health, 11, 156-60.

Tunkel, D. E., Bauer, C. A., Sun, G. H., et al. (2014). Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 151, S1-s40.

Tyler, R., Ji, H., Perreau, A., et al. (2014). Development and validation of the tinnitus primary function questionnaire. Am J Audiol, 23, 260-72.

Tyler, R. S., & Baker, J. L. (1983). Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48, 150-154.

Wetherell, J. L., Gatz, M., & Pedersen, N. L. (2001). A longitudinal analysis of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychol Aging, 16, 187-195.

No.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361-70.

Read MoreCookie settings

REJECTACCEPT

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | Stripe sets this cookie cookie to process payments. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_131443801_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| m | 2 years | No description available. |